Gore Range geology: A ‘trapdoor’ story

Summit County Correspondent

Vail, CO Colorado

ALL |

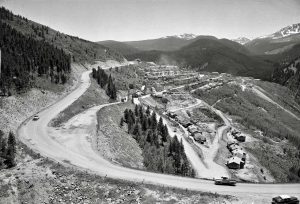

SILVERTHORNE, Colorado ” With the sawtooth quartzite of the Gore Range as a backdrop, Silverthorne geologist Randall Streufert sweeps his hand across the reaches of the Lower Blue River and describes the geologic origins of the mountains that border Eagle and Summit counties.

“It’s just a giant rock cork that keeps popping up,” he says, describing how the 1.7-billion-year-old rocks have been at the core of the Southern Rocky Mountains since the dawn of the continent.

“Every time there’s a compressional event, the Gore Range pops up,” Streufert says. “It’s an old piece of crust that rides up high.”

The peaks tower over Vail and surround Silverthorne have been shaped by unimaginable forces, as great slabs of the Earth’s crust skated into each other, crumpling and heaving.

Research on Gore Range peaks shows an interesting story: The bones of the local mountains are much younger than scientists thought until recently.

Support Local Journalism

Streufert explains how he and others use “fission track dating” to measure the age of exposed rocks. The newest evidence suggests that the valley may be part of a vast and recent rift system extending south into New Mexico, as the crust of the Earth spreads apart.

The landscape has been shaped by two styles of tectonic deformation, Streufert says, explaining how the story of the present-day mountains goes back at least 70 million years.

About 40 million years ago, those ancestral Rockies had been flattened by erosion, although the rocks of the foundation were still in place. Then, in another major geologic episode about 10 million years ago , the entire region ” including the Colorado Plateau ” was uplifted.

That’s when the rivers and streams started their work of carving down through the rock in places like Gore and Glenwood canyons, where the Colorado River cuts through the very heart of the range, giving the landscape much of its current look.

“We’re not sure what caused that uplift,” Streufert says, explaining that the entire western United States was affected by that event, known as an “epeirogeny.” “That has allowed the streams to exhume what we see today.”

“Colorado was under intense compression,” Streufert says, pointing out the contrast between the steep escarpment of the Gore Range and the much more gentle slopes of the Williams Fork Range across the valley in Summit County.

“Those older rocks were pushed many miles westward,” Streufert says.

Although it’s not always easy to see through the cover of vegetation, there are places where it’s easy to see different layers of rock touching as you hike up the Williams Fork peaks. On the lower slopes, you’re walking on those younger rocks that were once at the bottom of a shallow sea. As you near the crest of the mountains, you suddenly encounter the much older crystalline rocks.

Much more recently, a different kind of force has been shaping the local hills, Streufert says, explaining how, instead of experiencing compression, the crust of the Earth now seems to be stretching and spreading apart in parts of the West.

The Rio Grande Valley, the Arkansas Valley and the San Luis Valley are all signs of that tectonic extension, Streufert says.

“We’ve known about extension in the West for some time. What’s new is how much it has extended into the Colorado Rockies,” Streufert says.

The evidence has been uncovered through small-scale geologic mapping on a much more detailed level than what has been previously done. That includes Streufert’s work with fission track dating in the Gore Range near Silverthorne. Hiking up the peaks and taking readings of radioactivity, geologists can determine how long those rocks have been exposed.

“The higher you go in the Gore Range, the longer the tracks,” he says.

Steufert says the essential definition of the Blue River valley is a “half-graben,” the technical term for a valley that is sinking on one side, as the crust spreads apart (along the Blue River fault on the Gore side), but remains hinged on the Williams Fork side.

“Only the west side has down-dropped,” Streufert says, likening the geologic action to a trapdoor. Some of the dropping came as recently as five million years ago, a mere blink of an eye on the geologic time scale, he adds.

“We’re in a shallow, sediment-filled half-graben. Things are pretty stable right now.

“We’re not sure if the extension is still going on,” Streufert adds, explaining that those geologic processes don’t currently present any threat of earthquakes.

“There’s been no recorded seismicity on any local faults,” he says.

The jumble of foothills along the base of the Williams Fork Range includes debris from giant landslides that oozed down the slopes, covering up deposits of cretaceous-age shales. And Silverthorne itself is built on deposits of Blue River alluvium, huge deposits of boulders and gravel washed down over eons.