How Vail Valley local Dave Schneider won a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart in Vietnam

Schneider's tale of two medals spans bravery and blood

Special to the Daily

Honoring our Veterans

- Sunday: Dave Schneider, a Purple Heart and Bronze Star recipient, reflects on his Vietnam War experiences.

- Monday: Mac McMakin, an Eagle resident, flew a B-24 in World War II.

- Tuesday: Coverage from Monday’s Veteran’s Day ceremony at Freedom Park in Edwards. The event starts at 4 p.m.

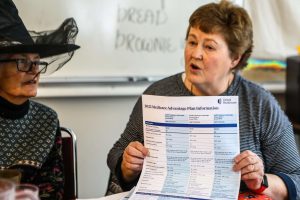

GYPSUM — Dave Schneider was speaking with hundreds of Eagle Valley High School students during a Veterans Day convocation when the question came again. A student pointed at two of the many medals on Schneider’s jacket and asked, “What are those for?”

Schneider smiled, pointed to his Purple Heart and said, “This one is for being shot.” Then he pointed to his Bronze Star and said, “This one is for keeping other people from being shot.”

Life and death really can be that uncomplicated, especially in the jungles of Vietnam, where bullets, bombs and the occasional python land on you.

Greetings! You’re in the Army

Schneider was a spry lad of 19 living in Texas when he received a letter with the salutation, “Greetings!” his draft notice. It launched a series of firsts:

- His first extended time away from home.

- His first commercial airplane ride.

- His first time someone tried to kill him.

- His first time pulling someone through withering enemy fire to safety.

- And, his first time and only time a python fell out of a tree and landed on him.

Basic training was in Fort Bliss, Texas, possibly the most misnamed spot in our spiral arm of the universe.

Support Local Journalism

“There wasn’t much blissful about it,” Schneider said.

When Schneider arrived it was 112 degrees. Guys passed out just standing in formation. Schneider, who thought he was in pretty good condition, was pumping pushups as fast as he could. His drill instructor kept up while doing pushups one-handed.

At the end of basic training, some soldiers were presented the then-new M-16, the preferred weapon of the Vietnam War.

“If they handed you an M-16, you knew where you were going,” Schneider said.

He spent a few days at home on leave, then flew to Oakland and on to Vietnam — the second commercial flight of his young life.

In December 1968, at the height of the Tet Offensive, he reported to the 11th Armored Cavalry unit.

“There was some big, bad stuff going on. They got us to the field very quickly,” Schneider said.

Schneider was assigned to a personnel carrier that did not actually carry personnel. It carried tons of ammo.

At night, soldiers circled up in a defensive position, like wagons in Western movies, except they surrounded themselves with concertina wire attached to phosphorous mines and claymore mines, pointed outward, away from them and toward the enemy. When the North Vietnamese tried to sneak into camp at night, the mines exploded.

Then there were the ambush patrols, which is exactly what it sounds like. Soldiers crawled away from camp and laid on their bellies all night, trying to draw fire or keeping everyone else from being ambushed, while ambushing the enemy instead.

Soldiers were draped with bandoliers — belts packed with ammo — that made them look like Rambo. Schneider decided that instead of carrying all that heavy ammo, he would carry the radio. The problem, he would soon learn, was that a Vietnam-era radio’s antenna waved through the air like a giant neon sign inviting the enemy to “drop your grenades here!”

“My second ambush patrol I had it blown off my back,” Schneider said. “That’s about the time I realized that this was a bad idea.”

His Purple Heart

The North Vietnamese had what Schneider calls “the home-field advantage.”

“The Vietnamese had been at war for 200 years. They were good at it,” Schneider said.

They planted land mines in the roads at night. The next day, American engineers with metal detectors removed as many as they could. That got tougher when the enemy started using plastic-cased mines, Schneider said.

The North Vietnamese also had help from the Russians and Chinese, Schneider said. Case in point: He said he saw a Russian tank driven by a North Vietnamese crew, rolling up a road.

“We were in lots of firefights that I didn’t know if we’d get out alive,” he said.

He was leading an ambush patrol when his unit was ambushed. That was no surprise, Schneider said. He was surprised, though, by how far a bullet will knock you back when you’re hit.

“From here to the fireplace,” Schneider said, sitting in his living room in Gypsum’s Riverview neighborhood and indicating a distance of 16 feet. “It’s not like the movies.”

The human mind can absorb all sorts of information in excruciatingly slow motion.

“I saw the bullet coming, and I knew I was not going to be able to get out of the way,” Schneider said.

It hit an artery in his lower body. Blood spurted 6 feet into the air. He knows that because that was the height of the bamboo his buddies in the other personnel carriers had to clear so the medevac helicopter could land.

They flew him to something like a military field hospital, where doctors operated on him for 10 hours. From there he flew to Tokyo. From there, most wounded soldiers were sent home. Not Schneider.

He was in his hospital bed reading Stars and Stripes, the military newspaper, when he perused an article saying that just because you’re wounded and in a hospital in Japan, that no longer means you’re going home.

He wasn’t. The Army sent him back to the jungle.

“I had eight months left in a 365-day tour,” Schneider said. “We saw lots of action, lots of casualties.”

His Bronze Star

When your tour winds down to less than 100 days, you’re a “two-digit midget,” Schneider said.

Schneider had two weeks left in country when American troops, including him, crossed into Cambodia. In its infinite wisdom, the Army decided howitzers would be in the center of an encampment. A howitzer shell is a massive bunch of gunpowder in a metal casing — the more gunpowder, the farther it could throw its projectile. The howitzer casings were open — no shells on them yet. Personnel carriers like the one to which Schneider was assigned circled the howitzers. Around them were ambush patrols. It is, as they say, a target-rich environment.

“That night they hit us with everything … small arms fire, artillery … everything you could imagine,” Schneider said.

Schneider grabbed a new guy and pulled him to safety under a trailer. The attack lasted all night.

“We suffered lots of casualties,” Schneider said, so many that massive twin-prop Chinook helicopters were necessary to evacuate the dead and wounded.

When the python fell on him

Schneider chuckled a little and said no Southeast Asia war stories are complete without recounting the time a python fell on you. Turns out, he has one of those stories.

Their personnel carrier was rolling through a rubber tree plantation, the trees set in neat rows except for one that had been planted out of line and they couldn’t get through. A personnel carrier is a hulking piece of steel on two tracks, so the driver tried to push the tree over and out of the way.

That stuff you hear about snakes being afraid of heights is not entirely true, Schneider said.

“This one wasn’t,” Schneider said.

The python was sunning itself in the top of the tree when the driver banged into it. The tree did not fall, but the python did, a couple dozen feet and right onto Schneider. Perspective is everything and perhaps panic made the python appear bigger than it was, Schneider said, but when it landed on him it looked like the biggest snake that had ever lived.

“It was this big around,” Schneider said, indicating with his hands something a little larger than a basketball.

Schneider said the snake slithered away quickly. He passed out.

Before the sun sets Monday on Veterans Day, local veterans will have visited 19 local schools, regaling students with tales of triumph and tragedy, reminding them that the U.S. military is on their side, and what’s a stake when a country drifts toward war.

Bronze Stars are won in wars. So are Purple Hearts.