‘It was never public land’

ALL |

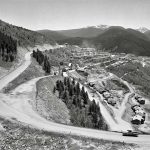

MT. LINCOLN – Where is the highest of Colorado’s high-end real estate? If you guessed Beaver Creek, Bachelor Gulch or Aspen’s Red Mountain neighborhoods, you weren’t even close – not in terms of elevation, at least.A one-time blue-collar worker from Denver owns the highest of the high end, the summit of Mt. Lincoln. At 14,291 feet, it’s Colorado’s eighth highest peak – and the state’s highest privately owned real estate.Maury Reiber, 75, has been buying mining properties on Mt. Lincoln and other peaks in the Mosquito Range, located between Fairplay and Leadville, since the mining bug bit him in the 1950s. A one-time sheet metal worker who later became a building inspector in Denver, he says he heard a television program saying that mostly it took money to make money. The only way a poor man could become wealthy, the announcer said, was to find deposits of gold, silver and nickel.To that end, he, his sons and other partners now own 211 claims, including 233 acres on Mt. Lincoln – and he’s still buying. Once patented, a claim becomes private property. Most claims were staked in the 19th century, before and soon after Colorado became a state. With relative anonymity, Reiber plugged away at his mines for years, hoping for the day when the price of silver and other precious minerals rises high enough to bring them back into production. At first he rarely saw anybody on his land. He had his first inkling of trouble in the 1970s.A hiker walked by one day and surveyed the operation. “You’ve got one hell of a liability issue here,” the hiker, who identified himself as a lawyer, told him. He didn’t mean it as a threat, only as an observation.Before there was ColoradoThe idea of liability has weighed heavily on Reiber and other owners of mines as steadily more hikers have been attracted to Lincoln and the three other fourteeners in the Mosquito Range whose summits – as well as much of the land down to timberline – are privately owned.

The Colorado Fourteener Initiative, a group that seeks to minimize erosion and other resource damage to Colorado’s 54 peaks that are 14,000 feet and above, estimates use is increasing 10 percent a year.But beyond his concern about somebody getting hurt on his property is an even greater frustration with vandalism, Reiber says. For this, Reiber blames four-wheelers. He reports broken locks, destroyed gates and no end to pilfering. Although the U.S. Forest Service owns less than half of the land in the Mosquito Range, the agency earlier this year acceded to the wishes of Reiber and others and began giving out sheets of paper to those who drop by the district ranger’s office in Fairplay.”All these peaks are PRIVATELY owned,” say the sheets. “Trails and roads going to the top of these peaks are NOT under USDA Forest Service jurisdiction.”That prompted a story in a Denver newspaper that contained a crucial error. It said the Forest Service had ceased issuing permits to climb the peaks. In fact, it never issued permits. How can it, when it does not own the land? For that matter, it does not issue permits to climb peaks in Colorado, although it does require registration at Mt. Massive, Maroon Bells, and several others. More disagreeable yet, says the ordinarily genial Reiber, are the comments posted at various Web sites. “People keep calling it public land, and it was never public land,” Reiber says. “It was private property even before Colorado became a state.”Up to timberlineThe Present Help, the mine atop Mt. Lincoln, was staked in 1871, five years before Colorado statehood. It was patented in 1882 and is believed to be the highest mine in North America. In conjunction with the nearby Russian Mine, which is located just below 14,000 feet, it was worked steadily until the federal subsidy for silver was withdrawn in 1893.The mines have been worked sporadically, as recently as the mid-1980s, when the Texas-based Hunt brothers tried to corner the world market for silver driving prices upward.

That yielded a lease for the mine and an air compressor on top. With only 65 percent of the air that is found at sea level, an air compressor has to work hard at 14,000 feet, Reiber says.Elsewhere in Colorado, the Wilderness Land Trust has purchased 5,218 acres alongside wilderness areas since 1992, and given the land to the Forest Service.In the Ouray-Silverton-Telluride triangle, a coalition of nonprofit groups working with local, state and federal governments have transferred 8,000 acres of private land to the federal government. A similar effort is now underway in the mine-pocked Elk Range between Aspen and Crested Butte.The goal of these efforts is to prevent development of the parcels, whether by mining or, more commonly, for backcountry cabins. The mountains around Breckenridge and Fairplay in particular are dotted almost to timberline with homes. Some are weekend and vacation cabins but others are the mountain equivalent of the American dream for locals.Near Aspen, as land prices escalate on the valley floor, developers are increasingly examining their prospects on remote mining parcels – much to the concern of local governments charged with dispatch fire trucks and provide other public services.”I can show you example after example of mining claims that are being developed as second-home sites,” says Doug Robotham, Colorado director of the Trust for Public Land. “It’s not a theoretical thing. And it goes right up to timberline.”‘Can’t say yes’But, while homes are also crowding timberline in the Mosquito Range, the situation is otherwise different. First, unlike Aspen, Breckenridge and other old mining towns, the skiing – and recreation-based tourism economy never rushed in to fill the void in South Park. Second, private lands among the high peaks are even more extensive.Allowing the Forest Service to cut trails through their properties might protect land owners from getting sued by injured hikers. However, the Forest Service would want a long-term commitment, says Sara Mayben, the district ranger in South Park.”We don’t want to put a lot investment into a trail that might be gone in 12 months,” Mayben says.

Reiber, for one, says won’t make a deal that’s irrevocable deal. He wants control of the mines come the day of soaring silver prices, he says. He believes this and other mines will become valuable again – if not necessarily in his lifetime, then at least in the lifetime of his heirs, he adds. Another possibility is purchase of the mines by nonprofit groups. “If the numbers were right I’d consider it,” Reiber says. “But it’s not going to be for peanuts, because of what’s underground and what’s in the (mine) dumps.”Meanwhile, several state legislators are interested in modifying Colorado law to protect landowners from liability for accidents at abandoned or idled mines. That would remove the monkey of liability from the back of mine owners. T.J. Rappaport, executive director of the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative, thinks an answer will soon be found. “I wouldn’t pretend to know a what the solution is, but there are enough people who want to climb in these mountains that somebody will come up with a creative solution that I think will prevail.”This summer, some hiking groups began contacting Reiber for permission to climb his peak. He has not granted it. He figures that if he does, it unequivocally makes him liable for their safety. “You just can’t say yes,” he says. “It’s so sad.”Vail, Colorado