Battling Mother Nature: How CDOT keeps I-70 open during snowstorms

SILVERTHORNE — Summit County thrives on snow.

It serves as the essential driving force that brings guests from around the world to enjoy the area’s ski slopes and backcountry chutes. But the snow also brings considerable challenges for transportation workers trying to contend with Mother Nature to keep the Interstate 70 Mountain Corridor open during the winter — one of the state’s biggest thoroughfares and an important economic driver for the entire region.

With businesses and industries relying on heavy traffic loads across Vail Pass and the Eisenhower/Johnson Memorial Tunnels, along with locals trying to get to work in treacherous conditions, officials understand what’s at stake, and take pride in their efforts to keep things moving smoothly.

“For me, the most rewarding piece is seeing the dedication of all of our employees and what they sacrifice on Thanksgiving and Christmas to get everyone where they need to go, and making sure school buses can continue to run and that EMS can get to the hospital,” said Kane Schneider, the region’s deputy maintenance superintendent with the Colorado Department of Transportation. “It takes a statewide effort to support.”

Local transportation officials have more than enough territory to keep them busy during a winter storm, and the delineation of responsibilities is important. CDOT breaks the state up into five separate regions for operations. Summit County is on the eastern boarder of Region 3, along with the rest of the northwest part of the state. The I-70 Mountain Corridor runs as part of a joint operations area with Region 1 to the east of the Eisenhower Tunnel, about a 130-mile stretch between Dotsero and Golden in all.

Support Local Journalism

The Region 3 section is further broken down into two maintenance areas: “Mary,” from Dotsero to the top of Vail Pass; and “Paul,” from Vail Pass to the tunnel. In the Paul area alone, workers are responsible for maintaining more than 800 lane-miles of roadway on I-70 and detour routes like Loveland Pass and Colorado Highway 131 among others.

With so much ground to cover, each new storm brings a unique challenge.

“We plan ahead, communicate during the storm, adapt, change and shift depending on what’s happening around us,” Schneider said. “There’s a lot of self-gratification in combating a storm, and being successful in keeping the road open in inclement weather.

Plowing ahead

The breadth of the operation requires considerable staffing and equipment.

There are about 85 employees between the two maintenance areas in Region 3. But during winter months there’s a concerted effort to better support the joint operations area, annually bringing in about 18 additional staffers from places like Pueblo, Craig, Greeley and Durango to stay for the season. More drivers can be shifted around from other areas when necessary.

CDOT officials receive daily weather forecast updates from an in-house CDOT meteorologist, and begin planning for winter storm events days in advance during resource and operational readiness discussions between the Paul and Mary areas and the rest of the state.

Snowplow drivers get their schedules and their set patrol areas ahead of time. They often work 12-hour shifts. They’ll slide into the seat of the plow and get on the road after a quick conversation with the previous driver about how the plow was running, and a maintenance check.

The job has its pros and cons.

“I love moving snow,” said Ken Garcia, one of CDOT’s local snowplow drivers. “Running the heavy equipment has always been a joy of mine, and something I like to do for work. And it’s a really good team effort between the plow drivers, state troopers, dispatchers and supervisors. Everyone is working with one goal: to keep the roads open. … But it’s pretty mentally draining. You’re focused, you’re on high alert watching our for changing road conditions, for other traffic and all sorts of stuff like that.”

In a given storm there are about 30 plows making patrols throughout the region, laying down liquid de-icer, salt and sand (picked up from a 1,200-ton pile at CDOT’s Silverthorne maintenance facility). Many plows are stationed on routes through high-priority areas like Vail Pass and the Silverthorne hill.

Still, there are always surprises, and much of the work is reactive. CDOT often has to move drivers around to replace sick employees or broken down plows, or to remove a “clogged artery” after an accident or major spin out.

“In a lot of ways you just have to deal with each situation,” said Todd Anderson, highway maintenance supervisor for the Paul area. “We do have some planning in place for how many trucks we have, and where they’re going to be. But when a semi crashes, you can’t plan for that.”

Road closures require efficient communication between CDOT crews and law enforcement to shut off the flow of traffic and get heavy tows and other equipment in place. Schneider said having experienced workers who know their turnoffs and can stage backed up traffic on appropriate grades to get it moving again quickly is key. Frequent driver turnover from season to season creates additional difficulties.

Poor weather can also be troublesome for plow drivers — whiteout conditions in particular — but Garcia and other CDOT officials said that other drivers on the road are often of bigger concern.

“This is such a high volume, high profile area,” Garcia said. “Everyone is coming up here to get their turns, and there are a lot of out-of-staters and people who don’t know what they’re doing. But what’s really the worst are the people who are too confident. People are speeding and trying to pass you on the shoulder, or creeping up on your formation. That’s probably the most challenging aspect. It adds a whole other element of danger you’re looking out for.”

When there’s snow in the mountains, there’s always a chance of avalanches.

Explosive solutions

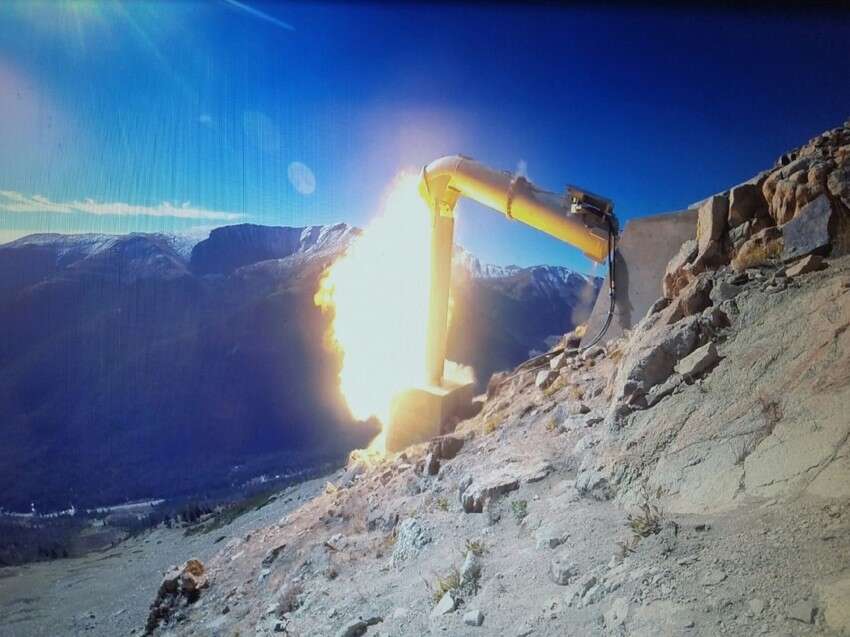

One vital aspect of CDOT’s winter operations is avalanche mitigation.

Historically, avalanche mitigation in highway programs has always been reliant on helicopters, howitzer cannons and “avalaunchers” firing explosives into the mountainside. But the department has begun to step back its dependence from traditional methods on advice from the U.S. Army, which provides the weapons, according to CDOT State Avalanche Coordinator Brian Gorsage.

“There’s more and more people out (in the backcountry), so shooting long-range projectiles kind of gets their hackles up,” Gorsage said. “Plus those missions take a while, and we’re having to handle live ordnance alongside the road. In the past 20 years there’s been a major step forward in mitigation technology, and CDOT has done a fantastic job jumping on board with that.”

Today, CDOT uses remote avalanche control systems, on more than 80% of avalanche operations along on the I-70 Mountain Corridor. Installations like the Gazex and O’Bellx systems create gas mixtures that allow for officials to trigger detonations at the flick of a switch. Earlier this year CDOT also installed two new Avalanche Guard systems, a cache and mortar system that launches explosives into designated areas.

Gorsage said the control systems are safer and provide officials with more flexibility, allowing them to conduct operations during early hours when traffic is lightest, or when a snowpack is at the peak of instability. CDOT officials have been tracking snowpack since the first snowfall of the season, and work closely with forecasters at the Colorado Avalanche Information Center to determine when avalanche chutes above roadways are in need of mitigation.

“Those guys are out and about in the field digging holes in the snow, getting a feel for the layering in the snowpack, and determining how much snow water equivalent, with combined wind and temperatures its going to take to produce a natural slide,” Gorsage said. “What we do is very different from what a ski area does. We’re trying to prevent the large-scale, natural slides from reaching an open roadway.”

Avalanche crews are given about 24 hours notice, wherein they’ll start organizing a plan internally to get road closures in place with law enforcement, and get heavy duty snowblowing machines ready for cleanup.

“You kind of cheer the success once the snow and debris is on the roadway under our terms, but the work is really just beginning,” Gorsage said.

The scope of avalanche mitigation work along different slide paths can vary considerably from season to season, and is typically focused along chutes that pose the biggest dangers to roadways. Gorasage said last winter CDOT performed a few missions on Vail Pass, four to the west of the tunnels, and another in the Tenmile Canyon.

Meanwhile, CDOT conducted about 25 missions on the Seven Sisters chutes near Loveland Pass.

“Those paths are so steep, and the road is built right in the track of the avalanche path,” Gorsage said. “So if you do get snow movement, it’s going to end up in the roadway. It’s high priority to make it as safe as possible. Our tolerance in those areas is very low.”

It takes a considerable effort across numerous individuals to help keep roadways open during the winter, and officials say community members can do their part by being prepared, driving responsibly and allowing their crews to work safely.

“What we ask is that our stewards give us the room and the respect we need to do our jobs,” said Schneider. “Be patient with us, be understanding. We have a very complex and unique job that can be dangerous at times. But we have the best interest of everyone’s travel plans in mind, and we’re not just closing down roads to inconvenience someone. If we’re closing the road down is means there are legitimate safety concerns.”