Colorado’s historic wolverine restoration will start soon. Here’s what the state’s plan reveals about how, where and why the latest predator restoration is occurring.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife clears two major hurdles toward its latest reintroduction

Adobe Stock/Colorado Parks and Wildlife

After a century-long absence, Colorado has a plan to restore wolverines in their natural habitat.

On Thursday, Jan. 15, the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission will vote on the final wolverine restoration plan alongside compensation rules for ranchers should livestock losses occur. The plan delves into where and how wolverines will be released in Colorado, as well as what people might expect from the rare predators.

Only a few steps stand in the way of seeing the small but ferocious species hit the Western Slope.

The last time a wolverine was documented in Colorado was in 2009. The male had traveled over 400 miles to Rocky Mountain National Park from Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming. It was the first sighting in the state for over 90 years after wolverines had been wiped out by humans in the early 1990s.

Why is Colorado reintroducing wolverines?

Colorado’s restoration effort is a historic one, becoming the first to attempt a formal reintroduction of wolverines — and it’s been a long time coming.

Support Local Journalism

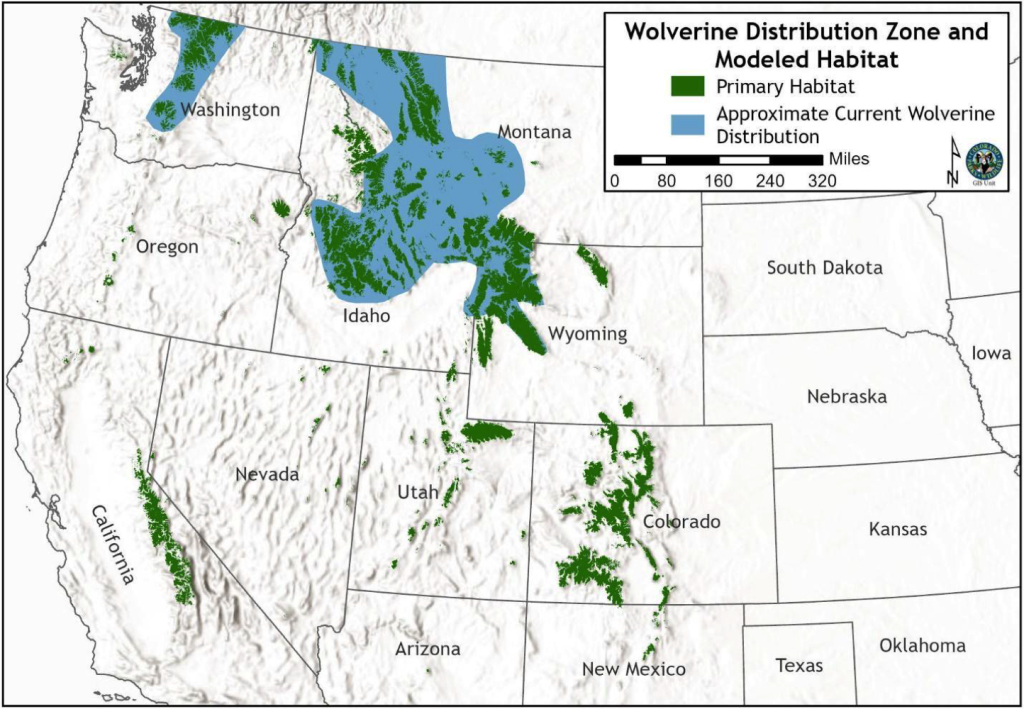

Wolverines were listed as state endangered in Colorado in 1973, but it wasn’t until 2023 that they were listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act following decades of oscillating legal challenges and petitions. Today, the species is found in North America across high-Alpine environments in Alaska, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming and all Canadian provinces west of Quebec.

Parks and Wildlife first contemplated reintroducing wolverines in 1998, when it was planning a joint restoration of wolverines and Canadian lynx. However, resource constraints led the state agency to pursue the lynx restoration in isolation.

Wolverines remained on the back burner until around 2010, when Parks and Wildlife’s lynx recovery was deemed a success. The wildlife agency worked in 2024 alongside several Western Slope lawmakers to create and pass a bill formalizing the restoration of wolverines.

Robert Inman joined Colorado Parks and Wildlife after 15 years researching wolverines in the Yellowstone region. Inman and Jake Ivan, a wildlife research scientist for Parks and Wildlife, are leading the wildlife agency’s wolverine program.

“With rare, threatened and endangered species like wolverines, a lot of time and energy goes into the courtrooms, and this has real on-the-ground potential for conservation success and advancement for this species,” Inman said in an interview with the Vail Daily. “It’s exciting to see that potential.”

Colorado has significant potential to sustain wolverines. According to Inman, there are around 85 records — from museums and archives — that place wolverines in the western United States in the 1800s.

“Almost a quarter of those were from Colorado,” he said. “Colorado has the biggest block of historical habitat that is not reoccupied at this time.”

The plan estimates that Colorado has around 11,500 square miles — slightly smaller than Belgium — of quality habitat for wolverines.

“Most of that habitat occurs on public land,” Ivan said, adding that the majority also overlaps with protected wilderness and roadless areas. “We think that we can do this and we can be successful without really infringing too much on the industries and land uses that already exist in Colorado. … But wolverines are going to have to make a go of it in 21st Century Colorado.”

Wolverines are solitary and territorial animals that exist at relatively low densities. Rocky Mountain National Park can likely house four or five wolverines, Inman said, so it’s estimated that Colorado could have a population of around 100 wolverines.

While this is a relatively small number, it would represent a nearly 30% increase of wolverines in the region, Inman said.

“We estimate that the Lower 48 — Montana, Idaho, Wyoming and Washington — probably have about 300 wolverines at this point in time,” he added. “So Colorado can be a very significant contributor to the conservation of the species in the western U.S.”

Where and how will Colorado release wolverines?

To hit Colorado’s capacity, the plan recommends Parks and Wildlife translocate up to 45 wolverines over three or more years.

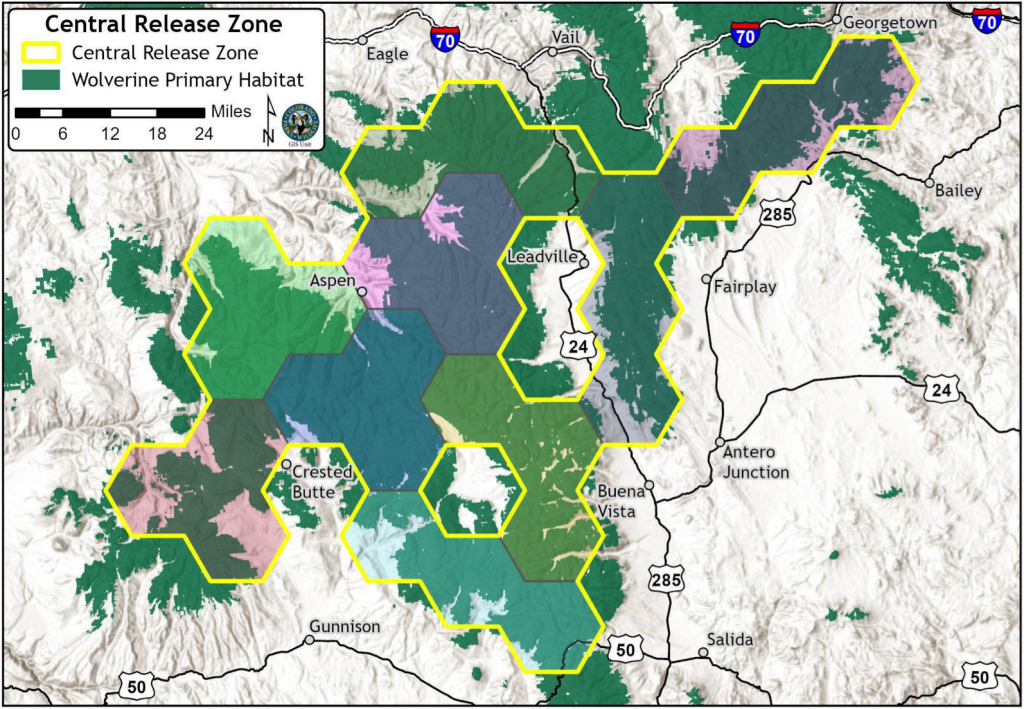

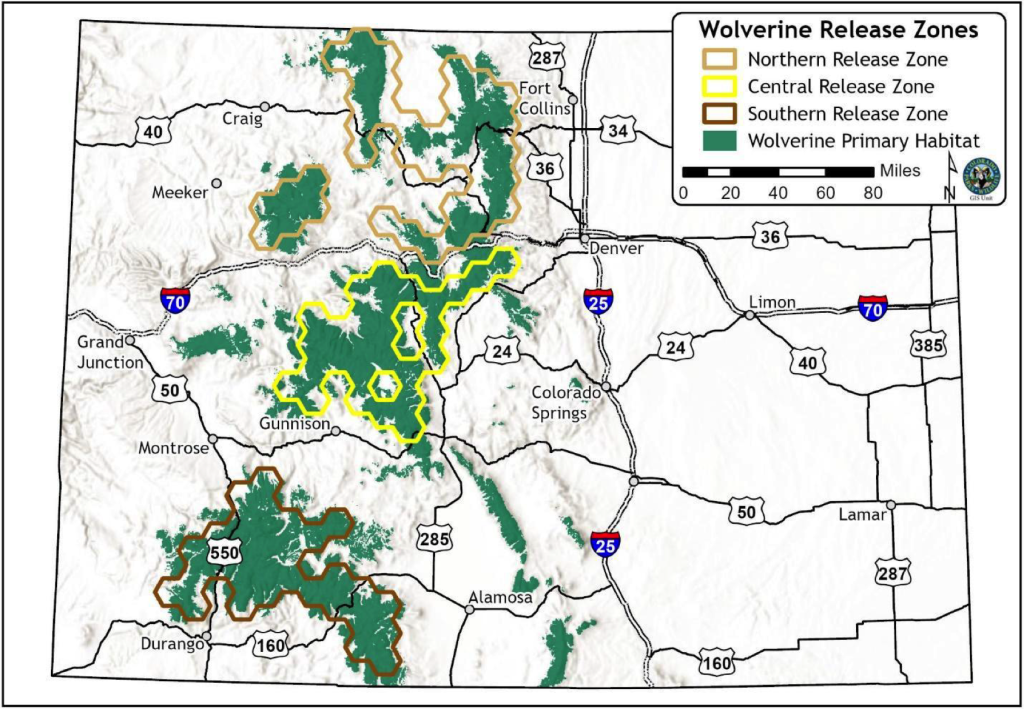

The first animals are expected to be released in the central mountains around areas like Aspen, Leadville, Vail and Breckenridge. Starting in the central zone — which spans nearly 4,000 square miles between Interstate 70 and U.S. Highway 50 — will place the wolverines in prime habitat, while also granting them flexibility to disperse to the north and south.

The plan has two more release zones, one north and one south, which will be used in subsequent years, depending on how the wolverines disperse and establish territories.

As the first agency to attempt wolverine reintroduction, Colorado is using a unique release strategy.

“We really pushed ourselves to think hard about the species’ biology and matching that to the conditions on the ground in Colorado at the time at which releases would occur,” Inman said. “We ended up not taking a standard approach where you just take a male and female and release them off the side of the road in good habitat.”

The most practical time to capture wolverines is midwinter, from November to January, when the majority of female wolverines are pregnant, Inman said.

Wolverines give birth in early to mid-February, and helping establish these litters in Colorado could have broader benefits for the restoration, he added.

“First of all, females that have young could stick to the area where we release them better than if they didn’t have a litter with them,” Inman said, adding that this could increase the population size more quickly and that wolverines born in Colorado would have a genetic advantage to survive in the state.

In order to support the litters, the plan recommends that the females be brought first to Parks and Wildlife’s Frisco Creek Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Del Norte. There, they will receive a veterinary examination, be fitted with GPS collars and be given time to recover from the relocation.

The plan recommends that half of the females be released around Feb. 1 — or when they’re around two weeks from giving birth — to den-like structures in the release zone. The other half will be held until after their litters are born and will be released in early June, when the young can travel with the adult female wolverine. In both cases, Parks and Wildlife will supply the animals with food sources at their site of release.

“In the natural world, an individual wolverine would have spent an enormous amount of time in the late summer and fall caching food at various parts of its home range that it would rely on to get it through the winter,” Ivan said. “That won’t be the case for those that we release in Colorado. So we are planning to provide carcasses for these individuals for a period of time after we release them.”

It may also incentivize the wolverines to establish a territory near the site of their release.

“It’s going to be really interesting to see whether they will stick to where we put them,” Inman said. “In my mind, that’s going to be the biggest challenge and one of the reasons we’ve emphasized the reproduction in litters as much as we have because we think that can have a potentially big, positive effect.”

In initially focusing on reintroducing females, Colorado could get male wolverines in a few different ways. The main challenge is that males often kill young that are not theirs.

“We will accept males from source populations if we capture them in the same place as females that we’re already bringing down, assuming that those are probably already a mated pair,” Ivan said. The male would be held and released from Frisco Creek with their mate.

“In a perfect world, we’ll be able to have those new litters on the landscape in Colorado and those can provide the males that we’ll need moving forward,” he added.

However, if neither of these situations plays out, Ivan said Colorado will have to specifically target males for translocation in the future.

The plan’s overall approach to wolverine restoration is to allow Parks and Wildlife to test and see what works best for the animals, Ivan said.

“We try to maintain a lot of flexibility, and this learn-and-adapt approach, as we go, because no one’s ever tried this,” he said. “And nowhere in the plan is that more prominent than the release strategy.”

Where will Colorado’s wolverines come from?

Colorado could likely be successful in sourcing wolverines from anywhere they exist, Ivan said.

However, given a choice, the plan ranks states and provinces that have similar habitat, predators and food sources to Colorado, which researchers believe could increase their chances of survival.

“Bears and wolves are present almost everywhere in wolverine range, but mountain lions are not found in a lot of the places wolverines are,” Inman said. “On the food side, marmots aren’t everywhere, so populations of wolverines familiar with marmots and how to hunt marmots would probably do better.”

Central and southern Alberta, central and southern British Columbia, and Idaho rank as the top five potential sources. No single location will provide all individuals in any given year of the reintroduction, and the wolverines will “trickle in from source populations throughout the winter, one by one,” Ivan said.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently prohibited Parks and Wildlife from translocating wolves from British Columbia, indicating they must come from a specific region in the United States. Luke Perkins, a public information officer for Parks and Wildlife, said the agency does not anticipate that this will impact the translocation of wolverines from outside the country, but that it intends to work with the federal agency on determining appropriate sources.

“Wolves and wolverines are very different species and don’t carry the same social challenges,” Perkins said, adding that if it cannot source wolverines from Canada, it is confident that the plan can be fulfilled from other sources.

What can Coloradans expect from wolverines?

Sightings of wolverines are expected to be infrequent yet memorable, Inman said.

“It’s a species that is incredibly rare on the landscape, no matter where they’re found,” he added.

The 20-40 pound predators are likened to a “very small bear, with a bushy tail” in the plan. Wolverines keep to themselves, establishing territories within high-Alpine environments. A male’s home range will often overlap with the territory of one to three females. Wolverines can disperse and move long distances, but Colorado’s reintroduction strategy is targeted at creating site fidelity from the start.

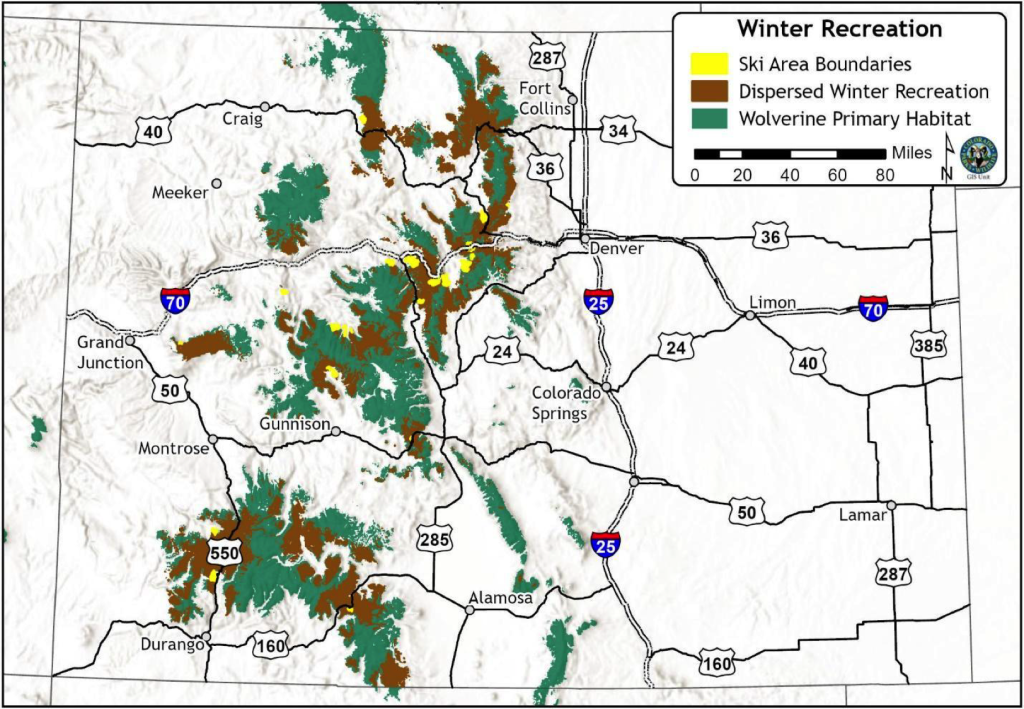

While most of Colorado’s wolverine habitat overlaps with protected and public lands — and away from humans — the plan identifies potential impacts from winter recreation, including backcountry skiing and snowmobiling. According to the plan, ski areas have a less than 1% overlap with modeled wolverine habitat, while dispersed winter recreation overlaps with around 20%. It is identified as an area in need of additional study.

“While (studies) indicate that Wolverines may respond to certain types and levels of recreation by altering their behavior to evade such activities, questions remain on the scale at which recreation is discerned by wolverines,” the plan states, adding that it could influence survival and productivity.

Wolverines are “opportunistic foragers,” scavenging carcasses and caching food. They can also hunt, primarily for small mammals, birds and medium- to large-sized rodents.

Colorado’s wolverine restoration plan requires Parks and Wildlife to develop a mechanism for livestock producers to be compensated for any losses caused by wolverines. On Thursday, the agency’s commission will vote on a wolverine depredation compensation process that aligns with how Parks and Wildlife reimburses producers for losses from bears and mountain lions.

The likelihood of wolverines killing or injuring livestock, however, is extremely low.

For at least 75 years, wolverines have repopulated in states like Montana, Wyoming and Idaho that have significant livestock industries, with few documented cases of depredation, Ivan said.

“There are two cases of wolverines taking sheep: one in Wyoming in the ’90s and one, a handful of years ago, in Utah,” he said.

None of those instances include cattle, as wolverines are not large enough to take on cattle, Inman said.

When will Colorado reintroduce wolverines?

Should the Parks and Wildlife commission approve the plan and move one step closer to formalizing the depredation rules — it will require a second reading to be codified — there are only two more steps required before wolverines can be released in Colorado.

First, Parks and Wildlife needs to create a plan for how it will communicate with stakeholders and county commissioners about the release areas, Inman said.

And second, the agency will need to obtain a special 10(j) rule from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Similar to Colorado’s 10(j) rule with the federal agency for wolf management, this will grant Parks and Wildlife the authority to manage the federally listed species as a nonessential, experimental population.

“We haven’t even begun that process formally yet,” Ivan said.

The wildlife agency is in the process of submitting a formal request to the Fish and Wildlife Service to initiate that process, which requires the federal agency to conduct an environmental impact analysis. It could take anywhere from three to six months to several years, ” depending on the scope of how it’s done, the area it covers and the degree of social angst accompanying the species,” Inman said.

For wolves, the process took a little over a year and a half.