Colorado’s ‘out of control’ costs tied to wolf attacks on livestock come under fire by lawmakers

Colorado Parks and Wildlife says it expects to pay around $1 million in 2025 claims for wolf-related losses, as changes loom for its online tracker

Andrew Maciejewski/Summit Daily

As Colorado continues the voter-mandated reintroduction of gray wolves, the state is continuing to refine and improve its process for preventing, investigating and reporting livestock losses from the predator. This could include changes to how it publicly reports wolf attacks on livestock.

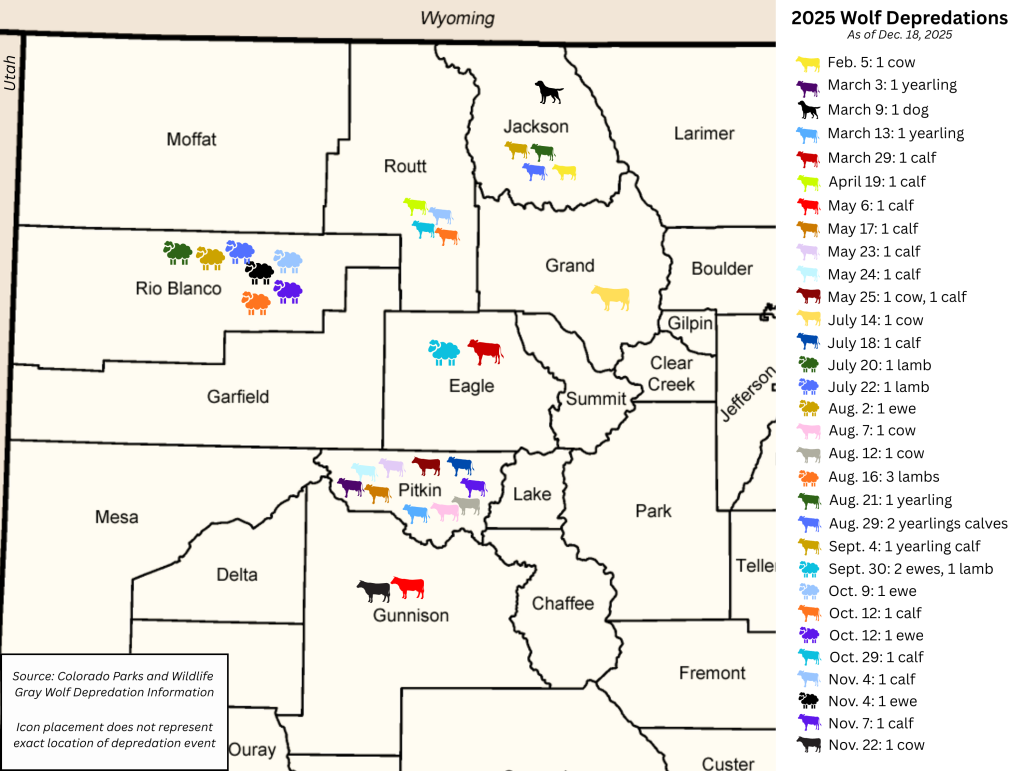

Since Colorado Parks and Wildlife began the gray wolf restoration in December 2023, it has confirmed 51 events of wolf predation on livestock, according to its online tracker.

Ray Aberle, private lands manager for Colorado Parks and Wildlife, explained why it’s difficult to completely eliminate wolf attacks on livestock during a Jan. 23 SMART Act hearing for the Colorado Department of Natural Resources.

Wolves are “highly intelligent and very adaptable,” Aberle said.

So, when it comes to deploying effective, non-lethal tools to mitigate conflict between wolves and livestock, “what works one place does not work the other necessarily, and you have to be quick, adaptable, and modify, and even within that, there is still a very high probability that loss could occur,” he said.

Support Local Journalism

“That’s why we have the compensation program,” Aberle said.

For losses from wolves, this program pays ranchers up to $15,000 per animal from the state’s Wolf Depredation Compensation Fund.

These funds cover not only direct losses of livestock and working dogs by wolves, but also indirect losses related to the predator’s presence on the landscape — the latter of which can include impacts on livestock conception rates and weight. Ranchers can also receive compensation for missing livestock in large, open range settings once a wolf depredation has been confirmed.

The payments for indirect losses are part of what makes Colorado’s program “the most comprehensive and thorough” compared to “any of the states that have wolf work going on,” Aberle said.

These indirect losses may also be responsible for driving the cost of the depredation program above what lawmakers originally projected.

Why are wolf depredation costs rising above predictions?

When lawmakers created the Wolf Depredation Compensation Fund in 2023, they set it up to receive an annual allocation of $350,000. Parks and Wildlife can also use federal dollars and non-license revenue from its wildlife cash fund to pay the claims should they exceed the fund balance. In 2024-25 — the first full fiscal year of Colorado’s wolf reintroduction — the agency paid over $608,000 to 13 producers.

A Jan. 5 news story from The Coloradoan reported that 10 livestock producers filed claims that exceeded $1 million for losses related to wolves in 2025.

During the SMART Act hearing, Sen. Dylan Roberts, D-Frisco, questioned why these costs are rising.

“How in the world did it get so out of control and so far away from what the department estimated losses were going to be?” Roberts said, adding that during the bill’s drafting the message was “there’s no way we’re ever gonna reach $350,000 every year.”

According to Aberle, however, the amount requested by producers is not surprising.

“I don’t mean this in any condescending way, but maybe part of the reason that number was arrived at originally is ’cause folks like myself weren’t part of the conversation,” he said. “If we look at large predator restoration work and the true cost of that in other states and other examples, it’s incredibly high.”

Aberle added that the $350,000 set aside annually aligns with what the agency might expect to pay in direct losses only, but likely does not factor in the compensation for those indirect losses.

Aberle said that the $1 million estimate was “very accurate of what we’re expecting to potentially pay out as we finish these claims that were submitted by Dec. 31,” amending a previous statement from the agency 15 days prior at a Joint Budget Committee that called the estimate “wildly inaccurate,” claiming the agency needed more time before it knew the amount requested.

Luke Perkins, public information officer for Parks and Wildlife, reported that the time “between these two hearings has given us better clarity on the amount of claims that have been submitted.”

Parks and Wildlife confirmed 32 wolf depredation events in 2025. Perkins reported that the agency is reviewing 26 claims relating to 2025 losses.

How Parks and Wildlife is publicly reporting wolf depredations, and how it might change

In addition to wolves, Parks and Wildlife compensates Colorado landowners and producers for damage to property and livestock caused by eight species, including mountain lions, bears and moose. Over the last five years, it has paid an average of 188 claims totalling around $603,000 — the majority related to livestock injuries or deaths caused by bears and mountain lions.

When dead or injured livestock are found, producers report the incident to their local Parks and Wildlife staff. Once notified, staff have 36 hours to complete an investigation. For it to be confirmed as a wolf depredation, the evidence must show a wolf was “more likely than not” responsible — evidence that can be challenged by time, environmental conditions, scavenging by other wildlife and more.

Aberle told lawmakers that over 170 of its staff members — including the nine damage specialists hired in the past year to assist in the process — are trained to conduct game damage investigations and have undergone “hours and hours and hours of additional training specific to wolves.”

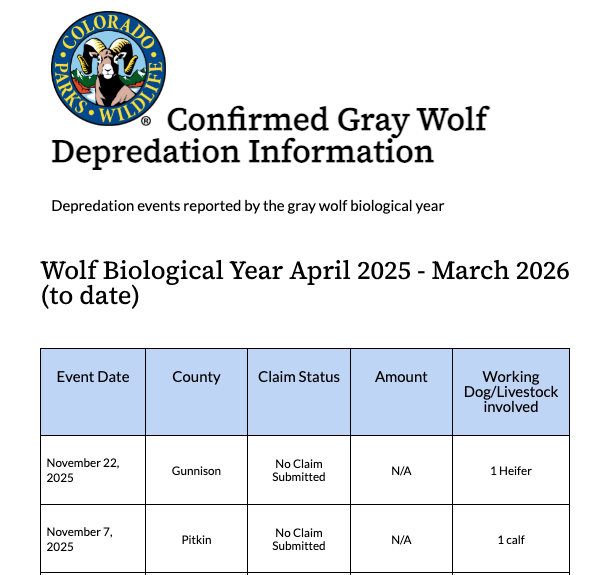

Since Colorado began its reintroduction, the wildlife agency has handled wolf compensation differently, including compensating for indirect losses, having a separate funding source and creating an online document to track confirmed wolf attacks.

The document provides information on when and where the depredation took place, what type of animal was injured or killed, and the status of any claim associated with the event and the amount paid to the producer.

“This sheet was started as a response to media and public inquiries regarding wolf depredation events in the state following the initial releases of wolves,” Perkins said. “There was an influx of these sorts of requests, and out of a desire for transparency, this sheet was created to gather information about wolf depredations as they were confirmed.”

Perkins added that “this is not a standard practice for other wildlife damage,” which is reported annually rather than on a rolling basis.

The sheet does not report the full amount of claims and payments made to producers, only showing payments made to producers claiming solely direct losses.

It does not show payments made for itemized claims and indirect damages, which is what the majority of producers are submitting at this point, Perkins said. These indirect payments are reported publicly in the annual gray wolf report, the last of which was published in June.

In 2024, Parks and Wildlife confirmed 19 wolf depredations on livestock. Producers submitted claims for 18. Nine received payments for direct losses only, which are reported on the sheet as totalling just over $14,900. However, nine are listed on the sheet as “claim received,” with no amount listed — meaning a payment was made for an itemized claim.

This includes the $583,000 in claims publicly reported by Middle Park producers, which were paid in full by the Parks and Wildlife Commission in July, despite a disagreement between the producers and wildlife agency over how it defines “missing” livestock.

When asked whether Parks and Wildlife is considering making changes to how it defines missing livestock following that discussion, Perkins said the agency “is not discussing regulatory changes to the wolf compensation program at this time,” but did undergo a collaborative process in 2025 to improve the claims process.

As Colorado’s wolf program enters its third year, Perkins reported that changes may be coming to the sheet.

“To help reconcile the shifting expectations of the program, and be responsive to producer needs, (Parks and Wildlife) has been going through an alignment process,” he said. “This online document is included among those that need review to ensure they align with organizational processes and the information (Parks and Wildlife) can provide/is valuable to the media and public.”